advertentie

Nieuws Archief

Social media

MYANMAR – Reports of deposed former Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s move to house arrest are “questionable,” her son said yesterday, adding he believed the ruling military junta wants to keep her location secret to deter resistance attacks on the capital as a civil war rages.

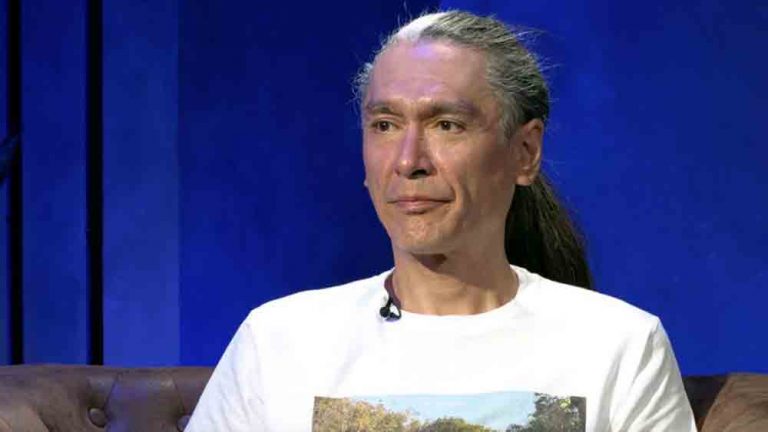

In an interview with CNN, Kim Aris cast doubt on recent reports in Myanmar local media, citing a military spokesperson, that 78-year-old Suu Kyi, the longtime democracy icon and Nobel laureate, had been moved from her prison cell ostensibly due to the unbearable heat. “It’s hard to know their motives. And as far as whether she’s been moved or not, that’s questionable as well,” Aris told CNN’s Anna Coren. “There’s conflicting reports coming out. In the past, they have said that she’s been moved to house arrest and that has proved to be completely not the case.”

Aris, who lives in Britain, is the younger son of Suu Kyi and her late husband Michael Aris. He said he believes his mother is “either still in prison or she’s in the residence of a military official.” “Her only house is a house that she has in Rangoon and she’s definitely not there,” he said, using the former name for Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city.

In comments reported by several media outlets last week, junta spokesperson Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun said: “Since the weather is extremely hot, it is not only for Aung San Suu Kyi … For all those, who need necessary precautions, especially elderly prisoners, we are working to protect them from heatstroke.” Suu Kyi has been detained in military custody since army chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing seized power in a coup on February 1, 2021, ending Myanmar’s brief transition to democracy and plunging the Southeast Asian nation into a raging civil conflict. Her condition and whereabouts have been kept tightly under wraps by the ruling junta and she has been photographed just once while attending a court hearing in the capital Naypyidaw in May, 2021.

Aris said his mother has been prevented from meeting with her legal counsel. “I believe they’ve been trying to meet for some time and nothing has come with that. As far as I’m aware, she’s not been able to see anybody outside of military personnel or prison personnel since, well, last year at some point, I think was the last time she saw her lawyers.”

As State Counsellor, Suu Kyi was Myanmar’s de facto leader for five years before being forced from power and detained after her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), was re-elected in a landslide election against military-backed opposition in 2020. She has been hit with a range of charges and is now serving a 27-year sentence following a series of secretive trials.

Aris recently told Reuters he believes the junta was using his mother as a “human shield” as the military fights an armed nationwide resistance determined to oust it from power. “As the fighting is getting closer and closer, I think it serves the military’s purpose for the resistance forces not to know where my mother is, so they find it harder to target strikes against the military in Naypyidaw. The less they know of my mother’s whereabouts, the harder it is for them,” Aris told CNN. Widespread public opposition to the military’s forcible takeover and bloody crackdown on protesters has only grown in the past three years and the pro-democracy resistance movement, which includes many of the country’s powerful ethnic rebel armies, now poses a legitimate threat to the junta. The military is facing battlefield and territorial losses on multiple fronts across the country, and there are reports of mass defections of soldiers. The military has since ramped up its violent attacks on civilians, with widespread reports of human rights abuses that amount to war crimes, extrajudicial killings, burning whole villages and indiscriminate use of airstrikes, according to human rights groups. It has also enacted a mandatory conscription law to boost its armed forces with compulsory service.

Since the coup, the junta has locked up more than 20,000 people considered to be political prisoners, according to local advocacy group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

Suu Kyi, who spent 15 years under house arrest during a previous military junta, has denied all of the charges levied against her – and rights groups and international observers say her convictions are politically motivated.

(CNN)…[+]